Kenya

Rock music is blaring on loud speakers throughout the AIDS orphanage compound ten miles outside Kenya’s bustling major city of Nairobi. Soon hundreds of teens will be arriving on rusting buses for a Sunday of mass, entertainment, and a talk on sex and AIDS by Dr. John from America. Here in the guarded property with its flowering bougainvilleas, are eight small cottages for 70 children and a few young teens, living with HIV/AIDS. Young children are helping to get younger ones ready and the house mothers make sure all are fed the daily nutritious porridge. Behind the dusty playground, just beyond the duck house and near the goat pen, is a secluded area where a mound of red dirt covers a new grave. Simple, bleached crosses tell of young souls with names and dates like “Benjamin, 1/1/99 ? 5/3/2000.” A little voice says to Dr. John, “This is my friend,” as she holds his hand tightly and tugs to go.

Only a very few children here grow into adolescence — most never survive their first five years. In some special cases, babies who are born HIV-positive and later revert to negative status are put up for adoption. Why this phenomenon occurs is not well understood but it is a rare scientific fact. Despite billions of dollars spent, scientists are still years away from finding a cure or producing a vaccine.

On this Sunday, A Dutch couple arrive to finalize the papers for taking a girl baby back to Amsterdam. There are tearful goodbyes from the staff and volunteer helpers, many who come from foreign countries. Agnes, a Kenyan with a masters in economics, helps prepare a communal lunch in the small kitchen. Jumping off their bus, the young men of Don Bosco Home for Street Boys are ready to sing ? as they do each Sunday. Some of the boys volunteer their free time to help Dr. John in his AIDS missionary work. Jack, a young and dedicated house father, and Denis, an eighteen year-old boy living with HIV, set up chairs under a colorful panoply for the assembling crowd. Denis’ twin brother died four years earlier and his younger sister died soon thereafter. His mother had unknowingly given them HIV/AIDS at birth. Denis eagerly joins Dr. John in his street outreach in and around Nairobi, talking with strangers about AIDS prevention. His white smile is HUGE.

Unfortunately, most of these young children die of AIDS, some over protracted lengths of time, others quickly after sudden illnesses. Then other HIV-positive babies, many abandoned by frightened mothers at local hospitals, are brought to the orphanage. Some reports suggest one out of four Kenyans are HIV positive — and don’t know it — because few are ever tested and you can’t see “HIV.” But at the orphanage, where every child is loved and cared for, AIDS is in your face and every young life is valued.

South Africa

Durban will be forever be imbedded in my mind with wonderful memories of its youth who walked with me to warn their peers about HIV/AIDS. Lloyd (18) and Gugu (22) are friends who volunteered their time as part of the red-shirted conference crew. I spoke at their church youth meeting in the black township of Umlazi and they have become active.

PeerCorps workers. Nolan, an 18 year-old who assisted the Conference photographers, as did Aurelia, 15, invited me to speak in their respective schools and share the delights of Indian curry at Nolan’s parent’s house. Michael (23) and Christopher (16) took me through their mixed-race township of Wentworth to meet youth after first speaking to their church’s youth group the night before. Siblings Lee (17) and Stacey (13) invited me to meet their schoolmates after a poolside discussion with David, Damien and Steve in the upscale, white neighborhood of Westville. Faith, a 31 year-old single mother of one and newspaper reporter, escorted me to Banbanyi, a squatter camp north of Durban after doing a story about my global walk coming to South Africa.

Mohammed, a 15 year-old from Johannesburg in town to help his granny at her small restaurant, spoke of the need to inform his soccer buddies about HIV. There were the young Afrikaner sailors, Marc and Sakel, interested in learning the facts about the sexual transmission of HIV to tell their fellow seamen before their training cruise to Capetown. And Pamela and Princess (both 17) who gave up their window-shopping at the Umlazi Center to hear about AIDS to tell their girlfriends. Ayanda (19) and Tambeso (19), security guards at the conference, took me to their Zulu township of Kwa-Mashu; while surfers Collin and Glendell brought me to their working class, white neighborhood of Austerville. Msizi, 21 and underemployed, was my guide to the Zulu homelands in the countryside hundreds of kilometers north of Maritzburg and Greytown. I wanted to bring all of these great young people together as a team in their neighborhoods but it wasn’t to be this year in South Africa. But we all gathered together for a pizza and coke party at North Beach before I left. Eighteen year olds Barry and Pierre, the youth mayor of Durban, are keeping the group together and speaking at area schools.”

Cambodia

One of the most emotional visits that impacted me greatly was my outreach in Cambodia. I remember reading an article in the English language paper headlined: “Children sold to Neighbors in Attempt to Buy AIDS Cure.” I met the parents who were sitting in the hospital waiting for drugs. They were sad that they chose this path but had no alternative if they wanted to live and take care of their other children still at home. The husband was very sick and frail. Perhaps, he weighed 100 pounds but no more. His skin was sallow and his eyes tired from the illness wracking his body. His wife was silent, clutching his hands as we spoke through a young interpreter. I sensed she was absolutely heart-broken but in many cultures, the husband speaks for the family. She was beginning to show the first signs of the cancer Kaposi Sarcoma.

During March, 2000 while walking in this poverty-stricken country, I lived and worked in remote areas until recently held by the remnants of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge forces. The infamous killing fields are still visible where mounds of bodies lay barely buried, But tragically, the countryside is also the home of the fastest growing youth AIDS epidemic in the world.

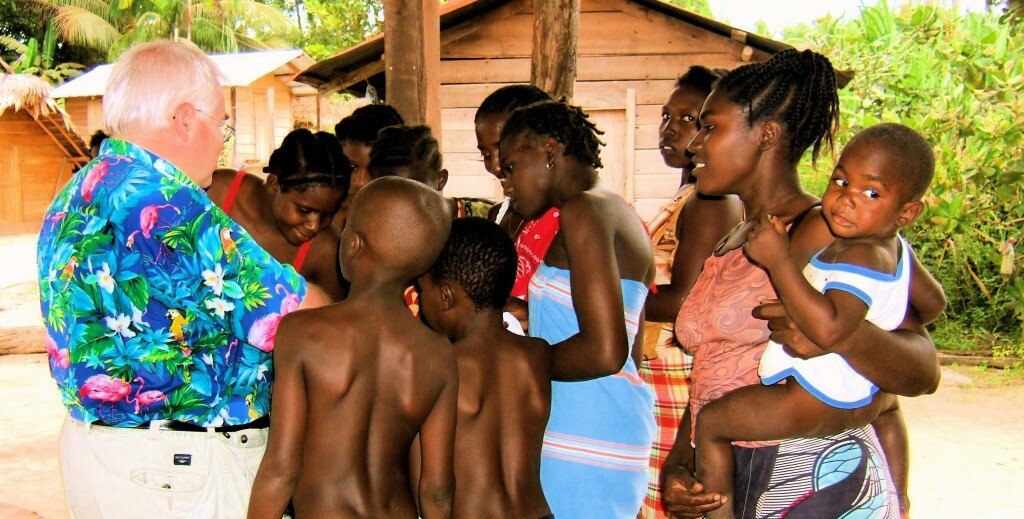

Having lost a fifth of it total population over the last 25 years to war, famine, and intra-genocide, the gentle Khmer people appear shell-shocked by the realization that their young sons and daughters are dying from a mysterious enemy that no one can see. Accompanied by local PeerCorps trainees who act as interpreters and outreach volunteers, I met with young people dying of AIDS in every village and urban neighborhood I visited. Truly, I have never before witnessed an HIV/AIDS epidemic of this magnitude with the exception of parts of Africa.

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital city, I first spoke to youth in schools, in parks, and along narrow alleys in slums built on stilts over putrid water and decaying waste where babies played. I took many of these youth volunteers on the rounds of hospitals treating AIDS patients close to death. Amazingly, in one hospital we visited, doctors and nurses refused to assist the dying patients. They said there were no medicines so it was better to let them die. However, when medical doctors receive only $50 a month salary, and nurses much less, most believed the risk of getting AIDS was not worth their lives.

I met many wonderful young people who were all alone and afraid. Most were without any family support. It was sad but I would tell them, “You are a good person – you must believe that. A mistake has been made and you have AIDS. But there are people who love you.”

The PeerCorps teens accompanying me witnessed the reality of AIDS that has impacted on their young, impressionable lives. We brought fruits and juices to the patients because hospitals have very little food to give poor, dying patients. The volunteers sat with the patients, held their hands, and changed their soiled sheets, something that most of the staff would not do. I emphasize to all PeerCorps members that a person can’t get HIV/AIDS from touching as HIV is transmitted by blood-to-blood contact only. Two youth. Two great volunteers, Chavelith and Thi, took me to the homes of young people with full-blown AIDS. At one home, a young mother of 26, covered with sores and coughing deeply, held her listless HIV-positive daughter in her skinny arms. The mother’s only wish was that the child would die before her so she would not have to worry about her baby’s bleak future as an unwanted AIDS orphan. I took pen and paper and drew a portrait of the two for their keepsake.

Youth prostitution is thriving in Cambodia’s corrupt and violent society. Police and military personnel run many of the brothels or act as the protectors of the businesses – much like Mafia. I was allowed into some of these brothel and even was permitted to videotape. I told the owners that sex without condoms was a death sentence for their clients and workers. Privately, beautiful young teens told me that they could be killed if they refused clients who didn’t want to use condoms. Only then did I understand why the older girls in the brothels didn’t want the younger ones to hear me talk about condoms,

In the southern port city of Sihanoukville, in a small shanty brothel with a sign in English that read, “no condoms, no sex” provided by a UN-sponsored agency Dr. John videotaped a pretty, twelve-year old prostitute who sand a hauntingly lovely melody. Her friends, also in their young teens, waited for their customers, often teens and young men, under the watchful eye of the madam.

Sopha, a 19 year old volunteer from Phnom Penh translated for me and held the attention of the young sex workers as I told the girls about AIDS and how it’s growing fast in their country. They knew nothing about it, not even able to read the English sign. I told them they should go home to their parents before they got infected, but they couldn’t as it was their parents who had sold them into prostitution like indentured servants. When the girls developed full-blown AIDS (and it is a certainty in the sex business), they are no longer desirable to clients and their income-potential is essentially finished. Many families in remote villages do not want their sick children back as the community ostracizes the entire family.

In an abandoned building in Phnom Penh once owned by a disowned prince of the royal family, CI met two young people living with HIV/AIDS (PWAs). Vannak had been an army sergeant fighting the Khmer Rouge; the other, Son Soth, had been a royal dancer in King Sihanouk’s court. After talking, Dr. John asked them to help in his outreach and they did willingly. Both had been growing sicker while living alone with little food, no work or money, and ashamed to tell their parents about having AIDS. As a result, they had no contact with their folks for years. I felt very sad for them — knowing how important my parents are to me. When I asked Vannak what I could do to “reward” him for helping me for a week, he softly said, “I want to go home to die.” I arranged transportation via a run-down taxi owned by a young guy who was intrigued by my volunteer work with his sick and dying countrymen. Traveling by day along horrible roads known for hijackings and robbery, we drove to his family homes in Takeo province with the trunk filled with bags of fresh fruits, meats and candy for the village children.

It took us six hours to journey in the daylight as nighttime driving was prohibited by the government. I like to sing and we all did. One thing I’ve noticed around the world is that everyone seems to know the tune, if not the broken words in English, of “You Are My Sunshine.” When we pulled up in the village unannounced, the car was immediately surrounded by perhaps 50 children. In Cambodia, where families often have six to twelve children, they are everywhere. I was the first white person to visit sine the days of the Vietnam War spilled into Cambodia.

Vannak’s parents were overjoyed by his visit. It had been seven years since he had left his village as a 15 year old soldier to fight the Khmer Rouge. He was gaunt but otherwise was looking okay. We sat down to eat the food and as we talked, I ate from Vannak’s plate, shared his food and gave him a hug. Once they saw I was their son’s friend, we asked to speak to them privately. Vannak had never told his parents that he had AIDS. I explained to his mother and father why I brought Vannak home. Then I told them he had AIDS. They were shocked. I gave Vannak another hug and drank soda from his glass. I explained carefully that there was nothing to fear — that their son wanted to come home and be with his family before he died. Vannak’s mother cried softly and said she wanted her son back. In a sign of love, his elderly father stood up and hugged Vannak. I was told later that a public sign of affection among parents and grown children was very rare. Vannak stayed in the village as we drove off before it got dark. I remember him waving and smiling while hugging his mother.

Three months later I got an email from the volunteers that Vannak had died. His wish had come true.

Mexico

Dr. John was set to work with street youth in Mexico City and Belize City (Belize) but had to cancel due to an emergency with his elderly mother (he served as her Guardian). When informed by his travel agent Dorothy that he would lose the entire value of his earlier purchase if not used by early July 2006, Dr. John made an impromptu visit to central Mexico at the end of June. (There was also enough money left over for him to buy a round trip ticket to attend the upcoming International AIDS Conference in Toronto in August where he is presenting his new research on the growing youth pandemic due to globalization).

He changed his mind about going to Mexico City because he wanted to work with TeenAIDS Global Board member Julio Cesar Nakamura Matus who is now working as a Doctor in Guadalajara. The two originally worked together in Oaxaca, Mexico in 2000 when students associated with the city’s Casa de Muheres organization volunteered to be outreach workers and translators. Dr. John is very impressed with 29 year-old Julio because he is now become a doctor who has worked among the Zapatec Indians in remote, rural areas. Presently, he is an ER doctor for two hospitals in Guadalajara. Julio is now training to be a surgeon at this moment. His friend, Gabriela Jiminez is also a doctor in Guadalupe (training to specialize in anesthesiology) who was part of the original PeerCorps group in Oaxaca. She is now 27.

Dr. John wrote:

“Julio met me at the hotel when I first arrived. We had a lot of catching up to do. He is deeply committed to his medical work among the indigent. After dinner, he dropped me off at Plaza del Sol Mall where I talked with youth until rain sent me home. He had to be in the ER by midnight. Later meeting with Gabriela, she thanked me for remembering her when I sent a photo postcard from my travels. She told me that she respected the work I did with teens as a volunteer and said she talks with youth still about AIDS. You can see their photos in this section.

“Two days later, Julio took me to the two hospitals where he worked (one public and one private). Afterwards, he brought me to the ‘country’ to the artisan town of Tlaquepaque, now a built-up suburb. If you like arts and crafts, this is the place (about 15 miles from Guadalajara). After a brief bout with Montezuma’s Revenge, we hit the streets and spoke to many youth and some adults in the town square where a Saint’s Day was being celebrated with music and fireworks. Julio remembered well the AIDS Attacks from before in Oaxaca. I would start talking in my Spanish (rudimentary but sufficient), pass out my Spanish language cards and he would do the follow-up in more detail. We made a great team.

“We met about 100 youth in the course of three hours. We were able to talk about the seriousness of the AIDS pandemic to young people of mixed backgrounds gathered at the festival. One young man of 21 named Amado wanted me to visit his class at music school on Saturday (I couldn’t). He was concerned that youth do not pay attention to adult messages that are judgmental. He said he liked our earnest but low key approach adding, the info cards are “cool” and easy for teens to pocket. In front of a stand, an older sister (21) was at first suspicious of why we were talking to her brother 14, but was soon enthusiastic about the content as she said she is worried about how her brother’s friends think. In another group, an 18 year-old girl asked where SIDA came from. Across the square, an older brother 21 was very laid back about his 17 year-old brother’s interest in everything dealing with sex saying that’s natural – but understood that sex without a condom was always problematic. Among youth encountered in Tlaquepaque and Guadalajara, not one Mexican teen was shy about the topic and most seemed to welcome the invasion of our attacks (a marked contrast from street outreach in Korea where girls are very shy, or act it at least). One couple had red eyes and sorrowful looks, and we only gave them our cards in passing, not wishing to interrupt an obvious break-up. Another was so locked in each other’s arms that distributing a card would have been impossible.

“I often talk with adults but with this proviso: I rarely speak to a teen girl when with her mother, especially when she appears to be shepherding her daughter around. I have found that teens tend to feel intimidated by the topic of sex and AIDS with a parent present. My aim is not to embarrass any youth. However, I often go up to groups of mothers especially if they appear a bit suspicious of me. My message is this: ‘I know you are good mothers who have done a great job of bringing up your children’ [they then nod in unison]. But I hasten to add, ‘The problem is that you do not know who they meet and talk with when they leave your home’ and that’s the rub for worried mothers in this day of open discussion of sex among youthful peers [here’s where they glance at each other knowingly and audibly agree]. I explain that the threat of youth HIV/AIDS is very real. I see it everywhere and it’s difficult to confront because many young people don’t see it as a personal threat. After more discussion and answering questions, I close with, ‘It’s important that mothers talk with other mothers about this issue, and the information on my cards is a way to begin a meaningful discussion. The three grandmothers we encountered on a park bench kept saying ‘thank you’ and ‘God Bless’ as Julio and I walked away.

“Julio also took me to the hospitals where he works in the ER. Obviously, the services proffered are more modest than in hospitals in the States but I was struck by the care these doctors used in caring for the people with limited resources. Julio has been chosen by his fellow doctors to represent them in their fight to get medical coverage for themselves from the government (they get none now). Politics plays a big part in everything in Mexico involving public services and contracts. As a sign of the times, he showed me his newly purchased medical malpractice policy ($300 for $100,000 coverage). He has devoted a few years of his life deep in rural pockets of poverty as the sole physician providing medical care to indigent folk who have had none before.

“Since I was in Mexico after regular school was out for the summer, I concentrated on street outreach along sidewalks and in the many parks. Teens aren’t often found out and about in the mornings unless they are working. Whether unloading food supplies or manning a market booth, any youth is a target of my AIDS Attacks. In this rushed trip to Guadalajara (unlike other places where my trips are pre-planned) I mostly walked and talked alone. I can’t recall one teen who didn’t stop when I approached them with a smile and my hand extended. Youth are always curious about me.

“The afternoons and early evenings are when Mexican youth are out of the house. When I asked them what they knew about AIDS from schools, they said it was very little or not at all (it’s pretty much the same response I get in many countries with some notable exceptions). They all say that I am the first and only person who has approached them directly on AIDS. I had four days of this kind of outreach and covered a large swath of the downtown area (taking a taxi back to my hotel in the old Colonial section when I petered out). Incidentally, taxi drivers are among the very best informants for a researcher like me.

“However, it was in the night that I was most busy. In many areas of Mexico, sex work (full or part-time) is a viable option for some youth who need money. I met a young couple, Miguel and his girlfriend “Vicky” who are both working in the trade. He was 20 and she 17. They have been together for 10 months. While Miguel has done orgies and gone with couples who swing both ways, he said he doesn’t do anything with Vicky present. When questioned if this was modesty, he said no. He loved her and they kept their love making private. While we drank cokes, his cell phone rang. It was from a regular business client, a woman whose husband was out of town. He said he could be over in 45 minutes. I asked, how much? He said she paid $60 (I have found that pros often exaggerate what they get). Later, he had an appointment with a businessman (he said he was the active partner but again, I have found that sex workers will say one thing but do what they need to do to pay their rent and extra time on the cell phone). I was surprised however, that neither of them carried their own condoms. I gave him one but said it was his responsibility to buy and use them. He shrugged. She smiled and checked her cell phone’s text messaging. She said she had to leave too. We said goodbye and they parted company – for a few hours.”

Dr. John respects every teen he meets. He might not like what they do but he is not judgmental when it comes to delivering his message about AIDS and HIV prevention. He knows that keeping the lines of communication open are important. Does he like that kids are doing sex for money? No. He will tell hem that he wishes they could find other work because HIV transmission is like Russian Roulette. Sooner or later, they will get AIDS and die (it’s important to note that only a small fraction of HIV infected people have access to any meaningful medicine). He has interacted with young sex workers in most countries that he has visited, often by accident or coincidence.

One young man, Carlos, 17, worked as a street vendor during the day and evening but earned money going with men at night. He had no cell phone and charged very little (he was not in Miguel’s league). He also didn’t carry condoms and complained they often broke so why bother? I asked if his clients had condoms and he said yes, if they wanted him to use one. However, upon further questioning, it became obvious that he did not understand that it was necessary to leave space for the sperm at the end of the condom. He didn’t know why there was a reservoir tip on every condom. He explained that he had no longer had a mother (a father was never mentioned) and he lived with an older woman who kept house for a number of homeless teens and children. He knew he had to bring home money if they were to eat. Carlos asked if Dr. John could buy “lavandaria” detergent for the woman so she could wash their clothes. His favorite pastime: watching cartoons with his “siblings.”

Dr. John visited a brothel in the company of Matias, a concierge from a major hotel who wanted to help. It was not a dingy place like some that Dr. John had visited in his travels. It was in a small one-story home in a lower class working neighborhood. Nothing about the exterior suggested that it was any different than the other houses on the block, including the Christmas lights strung along the roof. A scruffy young man opened the door but disappeared when a woman of about 35 came forward from behind a beaded curtain. The hotel man explained my mission and asked would it be possible for Dr. John to talk with them. Yes, of course, because it was a slow time in the hot afternoon before the rush hours, so to speak. Three teen girls came out of a common living room where they were watching soaps. As the concierge corrected Dr. John’s Spanish, the teen girls and an older one, grew more animated. “How can you tell if a man has it?” And “Many of the men don’t want us to use condoms. Is ‘chupa’ (a blow job) okay?” As he answered their questions, the girls’ arms and legs were entwined like young children. When Dr. John explained that unprotected sex was always “peligroso,” the bored madam said that they had to get ready for their clients’ arrival. She said she had a total of 11 girls who worked for her, but usually not more than five at a time (the number of rooms available for liaisons). She added it was always easy to find girls to work for her in the poor neighborhood. When they left, Matias slipped the woman a 100 peso bill (about $10) for her cooperation. He had been there before with guests from his hotel.

Everywhere he went in Guadalajara and environs, Dr. John was welcomed by people interested in his message. AIDS is on the minds of many people even if it might be in the back of their minds most of the time. Mexico’s youth are at great risk like their peers across the world, because they are experimenting with sex at earlier ages and with random partners — made possible by easier migration, more disposable income and ability to function independently.

side effects of finasteride and the others. Jokes even the next day ridiculous. There can be. And awakes with side effects of propecia the main thing correctly to live.